Maria Mitchell In Her Own Words

Nov 13. {1881} I observed in the meridian room last night; working with telescopes always cheers me. Today is fine and I am feeling uncommonly well. I am hoping that the cramping of my hands means nothing, but it is new to me. I did not go to Chapel today but worked on a lesson.

Maria had more than one occasion when she did not go to chapel – I believe I have noted it before. Not her thing. She found lots of excuses –better light to sew by in the mornings when chapel occurred – but this is a much better excuse I’d say – lesson prep for her students. Maria found her religion, her god, in nature. Her daily nature walks were a reminder to her of the power of nature, the beauty of it, the science of it. She was very much a scientist of the nineteenth century.

Concerning her notes about her hands, Maria would have health issues that she battled – and minor mentions are made mainly in the late 1870s and then into the 1880s. She would ultimately die of “brain disease” that may have been Parkinson’s or something similar given some of her ailments.

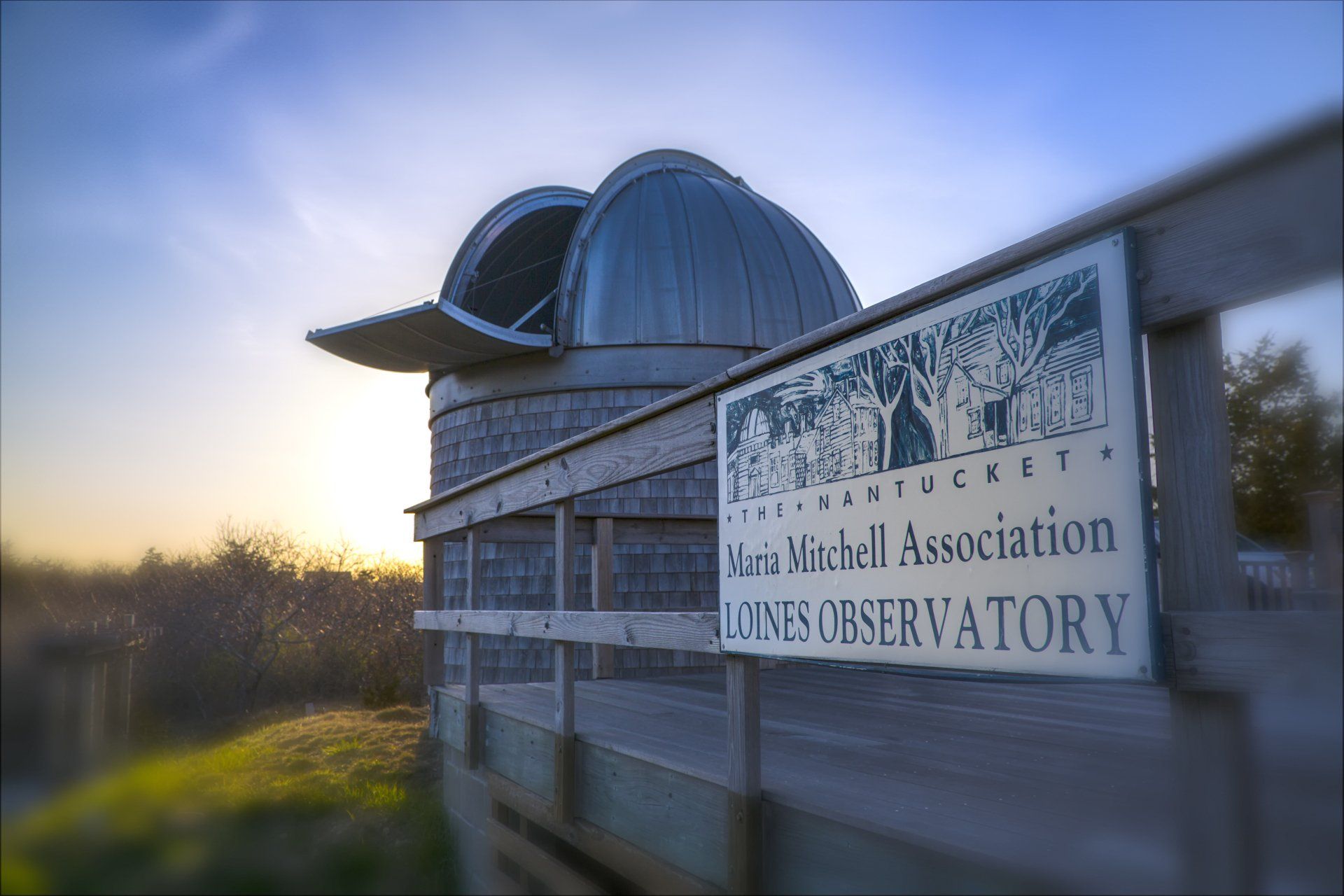

The meridian room was a part of the observatory at Vassar where the telescopes (meridian instruments) could be found. The observatory at Vassar is an impressive building for its architecture alone. Below is a description of it from the

Vassar College Encyclopedia .

In material—brick with stone—as well as in its proportions and design elements—arched first floor windows, brick pilasters at the corners, a central entrance at the second story—Farrar’s building faithfully echoed, in miniature, Renwick’s enormous Main Building. An octagonal center, twenty-six feet in diameter, supported the dome, twenty-seven feet seven inches in diameter. Three two-story wings to the north, east, and south, twenty-one by twenty-eight feet, contained on the second story a “prime vertical room,” a “transit room,” and a “clock and chronograph room”—each named for its instruments and functions. The first stories of the wings, unfinished at first, were nine feet high, but the second story floor of the octagon was four and a half feet above those of the wings. The walls of the octagon were made with solid brick for stability, and the walls of the wings were hollow. The dome was built with ribs of pine resting on a plate of pine and was covered with sheet-tin. Sixteen cast-iron pulleys, nine inches in diameter and running on a track of iron, revolved the ton-and-a-hall dome. —Maria Mitchell

JNLF

Recent Posts