Judith Macy, Island Entrepreneur

A few months back, I posted a blog about Nantucket’s infamous daughter, Kezia Coffin. While she may have been someone of our past that many islanders are not fond of, her sister, Judith Macy (1729 – 1819), was a bit better and a Quaker in good stead. Like her sister, Judith was an eighteenth century entrepreneur but one who did not have a monopoly on her fellow islanders and who played fair – as far as I can see. Unlike many of her sister islanders however, Judith’s husband was at home.

Widowed after just two years of marriage, Judith married second husband, Caleb Macy, a man who had faced many financial failures in his short life. Like most island men, Caleb had gone to sea but did not fare well – it was a claim of the fact that his health did not cooperate with the life found at sea. According to their son Obed, Caleb found not just a life partner and someone to tend to their household and children in his marriage to Judith, but he also found someone to help him in his business dealings.

With ten children and her husband’s shoe making business to assist in, Judith found herself taking care of several men who boarded with the family. Sometimes as many as twelve men joined her family of twelve at the dinner table. These men were likely Caleb’s workers. In her daybook, which is in the collection of the Nantucket Historical Association, Judith kept a fairly detailed, if sometimes scattered, account of items purchased and sold, work completed, and records concerning her boarders between 1784 and 1805. Judith employed at least one of her daughters and several other women to spin wool, which she sold for profit. In some cases, it appears that Judith hired out a daughter to do work, and she sold goods to her sons, several of whom were prosperous island merchants, including Obed.

The details of the lives of Judith and her sister, Kezia Coffin, and Mary Coffin Starbuck serve as some of the few examples of what life was like for women and the role they played in society and the island economy on Nantucket in the eighteenth century. In reference to her boarders, Judith kept details of when they “came here to bord (sic)” and the number of meals they ate during the week. For example, on the fifteenth day of the sixth month 1800, Judith recorded that boarder Daniel Gifford “Eat 2 meals this week” and on the sixth day of the seventh month 1800, he “Eate (sic) 7 meals this week.” Judith “sold corn out of the crib,” nails, molasses, “scanes of yarn” – likely created in her home by herself, her daughters, and other women she hired – and candles. She even made a record of candles that she sold to her son Silvanus. Judith seems to have played the role of supplier and seller for Silvanus, selling wool for him and making him sign off on his acceptance of the payment by having him make a notation in her daybook.

Judith’s daybook served, not just as a record of what was happening, but as an account book for what she and people in her employ produced, what she sold, and her other income producing activities. She kept track of how many hours people worked for her and on her behalf for others in her daybook. It also appears that she may have made loans to people so that they could pay the rent on their homes (Perhaps owned by her sister?). Judith Macy even kept a detailed tally of personal items she loaned to others – surprisingly, even noting the items she loaned to her own children. Judith’s husband obviously did not disapprove of her work since she continued working for so many years – almost right until her death, it appears. Meager evidence indicates that Caleb’s shoemaking business was successful and he owned a large amount of real estate on the island, so he did not need his wife to work.

Unlike her sister, Judith was a Quaker in good stead – serving on various committees, even serving as the clerk of the Women’s Meeting. Thus, her Quaker beliefs and those of her husband may have furthered her ability to conduct so much business as a woman. Judith may have been influenced in part by her sister’s entrepreneurial skills, but she was also living in a community that did not believe in idleness and needed everyone to work so that the island, its people, and its economy could survive. In some respects, the island took this frontier style of life even further, allowing women to take on important roles within the community.

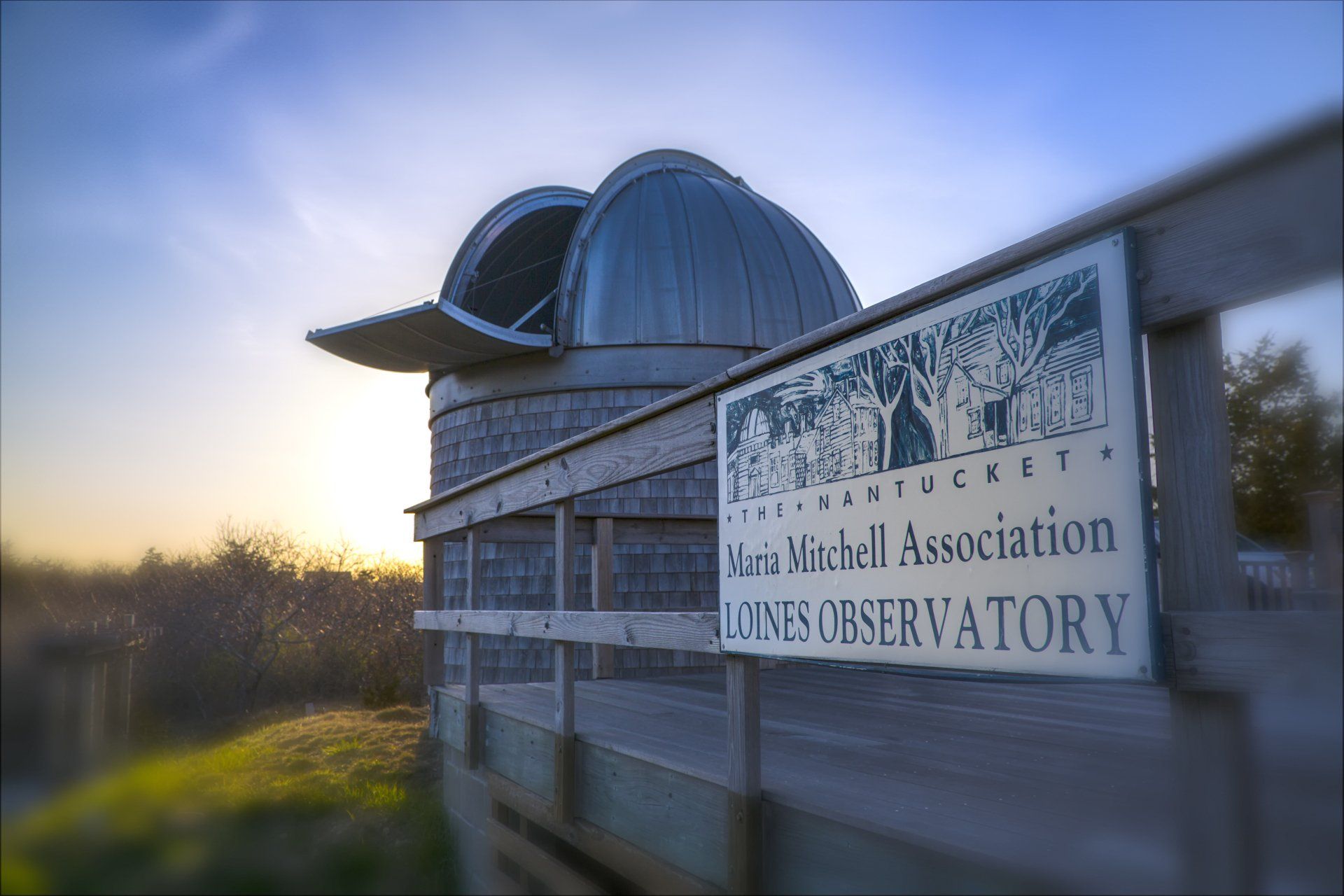

The image you see here is her home near Sunset Hill.

JNLF

From:

The Daring Daughters of Nantucket Island How Island Women from the Seventeenth through the Nineteenth Centuries Lived a Life Contrary to Other American Women by Jascin Leonardo Finger

Recent Posts